A Leading Voice: A Polio Survivor's Story

Guest blog by Safia Ibrahim, UNICEF Canada Special Vaccination Representative.

At times I catch myself staring at my 10-year-old in admiration as she reads a book at bedtime or does her math homework. There is nothing extraordinary about these skills – they are the norm for a Canadian child in the fourth grade. But compared with my experience as a young girl living in Somalia with a disability from polio, there’s nothing ordinary about it.

I contracted polio as a toddler. It is a very contagious virus that attacks an infected person’s brain and can lead to paralysis. This was the future my parents set in motion when they opted not to have me vaccinated. As a result, I spent the first six years of my life crawling. In those days I remember waking up at dawn to brush my teeth, comb my hair and get dressed for the day, just like other children in my neighbourhood, The difference was the other children had a purpose for this daily routine and I didn’t.

I would sit outside our front door and watch my peers walk to school with their thermoses full of ice-cold water and multi-coloured school bags on their backs. I would wave with a smile but internally I wanted to run to join them.

At the age of 7, I knew two things for sure: One, I desperately wanted to carry a thermos full of water and a backpack full of books of stories, ideas and math, alongside my friends. Two, these symbolized something life changing that I was kept away from because of my disability, because I was a girl. I was missing out on learning life-altering skills such as fractions, reading and even something as basic as writing my own name.

In Somalia, children with disabilities are invisible, even today. They are considered defective, cursed or a blemish on the family, hidden from society. For these and other reasons they face numerous barriers, including inaccessibility when it comes to their physical environment. Also being a girl meant I was treated as a second-class citizen -- boys with disabilities would get the available resources first.

When the civil war broke out in Somalia, I remember being extremely afraid. I didn’t know what was going to happen to us. We fled. We became refugees of war. What choices would others again make on my behalf? What barriers would I continue to face that would continue to exclude me from my dreams? Barriers that would take me even further away from getting to walk down the street with my friends with my thermos and backpack to school to learn.

We left everything behind. Everything, including that life.

When we settled in Canada, I received medical treatment for my disability for the very first time. I was fitted for leg braces and given crutches.

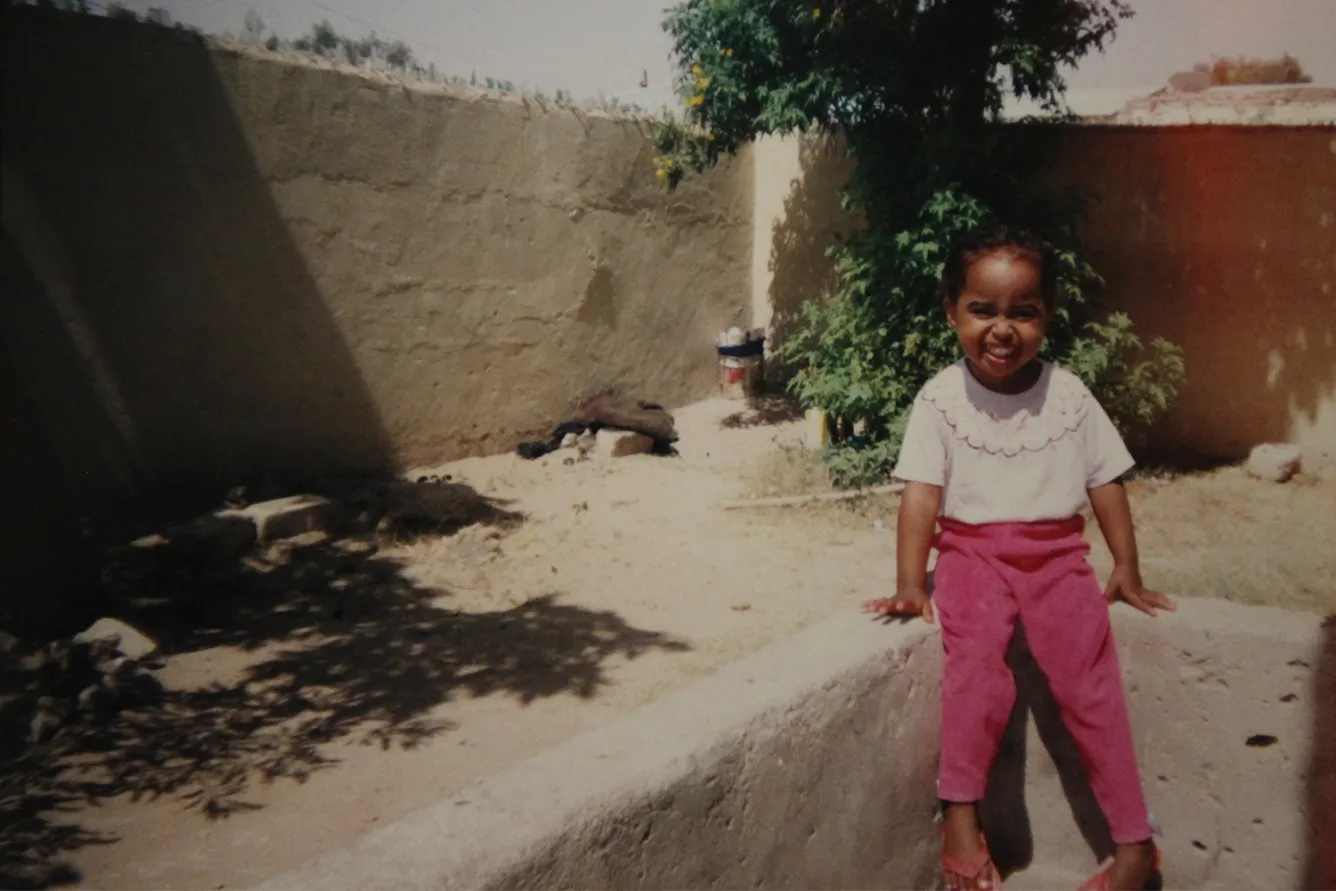

On Monday, November 5th, 1990, I combed my hair, brushed my teeth and got dressed. I meticulously chose my outfit for the day, I folded and unfolded the shirt and pants over and over. I packed my new pink My Little Pony backpack with a purple notebook and a purple pencil case. I counted each pencil crayon. There were 24. I was overwhelmed with excitement. My heart was racing, my palms sweaty. I caught the bus. It wasn’t long ride but it felt like an eternity. At 8 years old, with my backpack on and thermos in hand, I finally reached the place that had only existed in my imagination.

There were five multi-coloured round tables each with four plastic chairs. There was a fish tank with goldfish and what I later came to know as the alphabets on the wall. There was also children’s drawings on the windows and a rocking chair in the corner.

My teacher, an older woman with dark brown hair and a soft-spoken voice, guided me to a blue table, the one nearest to her desk. She showed me a label on my chair with the similar to the letters on the wall. “Safia,” she said, pointing to each letter and back at me. I had a seat at the table, this refugee girl, this polio survivor with a disability. This girl went on to be a leading voice in her community in Canada advocating for access to vaccines and polio eradication for children around the world.

My own children inspire me. They capture my admiration as they read or do their math homework, sharing with me their days full of walks to school with friends, thermoses and backpacks full of books and pencil cases.